Public Forum Debate

Public Forum Debate (PFD) involves two teams, each with two students, debating an issue of current interest or policy. A judge decides which two-person team wins the debate. Public Forum debaters across the nation debate the same issue, referred to as the resolution, for one month. One side, the PRO, argues that the resolution is true, while the other side, the CON, argues that it is false.

Examples of past resolutions include:

Resolved: The United States ought to replace the Electoral College with a direct national popular vote.

Resolved: The United States should lift its embargo against Cuba.

Resolved: In order to better respond to international conflicts, the United States should significantly increase its military spending.

Resolved: On balance, the benefits of the Internet of Things outweigh the harms of decreased personal privacy.

|

What happens at a tournament?

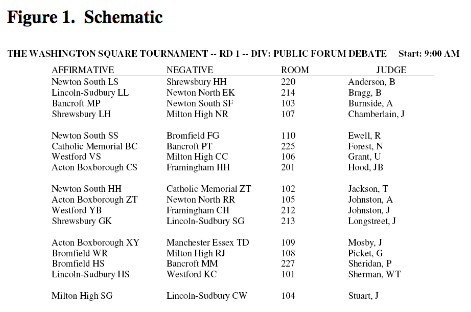

A tournament consists of a series of rounds. At a typical tournament, there will be four “preliminary” rounds during the day. At some tournaments, the teams with the best preliminary round records will advance to a semi-final or final round at the end of the day. During each preliminary round, each team debates another team. For example, if there are 80 two-person teams entered in PFD at a tournament, there will be 40 separate debates taking place during each round, each typically in a separate room. A schedule referred to as a “schematic” announces the round. For each debate taking place during that round, the schematic (Figure 1) lists: (1) the two teams debating, (2) the room where the debate will take place, and (3) the judge. |

What happens in a debate?

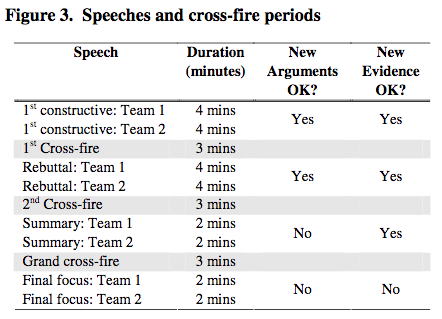

The debate consists of a series of speeches delivered by each side. The debaters also engage in “cross-fire”, during which debaters from the opposing teams question each other. (Figure 3) summarizes the sequence of speeches and cross-fire periods during the round. This information also appears on the ballot. (Figure 3) also summarizes the guidelines on when new evidence and new arguments can be made in the round.

Each team also has 2 minutes of preparation time to use throughout the entire round. For example, Team 1 may choose to confer for 20 seconds after the first cross-fire prior to starting their rebuttal. In this case, Team 1 would have 1 minute and 40 seconds of remaining prep time. What happens during each speech and each cross-fire can vary from round to round, but in a typical round, you will find the following:

The debate consists of a series of speeches delivered by each side. The debaters also engage in “cross-fire”, during which debaters from the opposing teams question each other. (Figure 3) summarizes the sequence of speeches and cross-fire periods during the round. This information also appears on the ballot. (Figure 3) also summarizes the guidelines on when new evidence and new arguments can be made in the round.

Each team also has 2 minutes of preparation time to use throughout the entire round. For example, Team 1 may choose to confer for 20 seconds after the first cross-fire prior to starting their rebuttal. In this case, Team 1 would have 1 minute and 40 seconds of remaining prep time. What happens during each speech and each cross-fire can vary from round to round, but in a typical round, you will find the following:

|

Constructives:

These speeches, which are typically prepared before the round, stake out the basic position for each side. Debaters will advance two or three reasons why you should support their side of the resolution. They may also define critical words in the resolution to help frame the debate. 1st Cross-fire: The speakers who delivered the 1st constructives take turns questioning each other. The purpose of cross-examination is clarification, not argument; the questioner should always question and avoid statements. Rebuttals: These speeches, delivered by the debaters who have not yet spoken, typically attack the case presented in first constructive by their opponent. The Team 2 rebuttal may also respond to attacks made in the Team 1 rebuttal. 2nd Cross-fire: The speakers who delivered the rebuttals question each other. Summaries: Each side identifies and defends key points in the debate. The summary speech can introduce new evidence but cannot introduce new arguments unless they are in response to opponent arguments introduced in rebuttal. Restricting the introduction of new arguments in summary helps ensure that the opposing team has sufficient opportunity to respond. Use your judgment to determine if arguments in summary are new, and if so, if their introduction is valid – i.e., has the argument been introduced in response to a new argument in the opponent’s rebuttal. If the argument is new and not validly introduced, disregard it. Grand Cross-fire: All debaters engage in a four-way question-and-answer session. Final Focus: Each side explains why they have won specific arguments and why winning those arguments implies that they have won the debate. Final Focus should introduce neither new arguments nor new evidence. The new evidence prohibition can be relaxed if the new material is presented in response to a first request for that evidence made in the opposing team’s summary speech or during grand cross-fire. |